This is the second of two articles reflecting on iconography and pornography based on conversations in the USA with an iconographer, Anne, and two parish priests, Fr Peter and Fr Paul, all from different parts of the country. You can read the first article here.

Image and modern western society

In relating the concept of the image in iconography and pornography, a possible avenue is to explore whether there is any link between the iconoclasm in the background of our historically Protestant countries and the rise of pornography, and whether these same societies are now developing a growing dependence on ‘image’ above ‘word’. Anne sees a connection in that “we are physical beings, and when we’re struggling with physical issues, it’s difficult to find something to hold on to when there’s no visible image before our eyes.” She compares it to the parable of the ‘empty house’ where a demon is expelled, but since there is nothing to take its place in the soul, it returns with seven more (Mt 12:43-45).

A catechumen interviewed by Frederica Mathewes-Green for her article ‘Men and Church’ agreed, writing “that he was finding icons helpful in resisting unwanted thoughts. ‘If you just close your eyes to some visual temptation, there are plenty of stored images to cause problems. But if you surround yourself with icons, you have a choice of whether to look at something tempting or something holy.’”

Fr Paul does not necessarily see this connection between traditional Protestant iconoclasm and the rise of pornography, as his experience shows him no discernible difference between the patterns of Protestant, Catholic and Orthodox people in terms of the potential to become addicted to pornography. He also points out the increasing tendency of Protestant ministers he knows to make some limited use of icons in their own personal prayer, if not in church. Certainly it would be interesting to study the impact and extent of pornography across historically Protestant , Catholic and Orthodox cultures to see if the undifferentiated impact of pornography that Fr Paul notes on individual persons can also be extended to cultures.

Anne has seen in her lifetime the growing dependence on image above word as television and video games have taken the place of books and the spoken word in radio. She notes the significant impact images of all kinds have on our lives. For example, those with food addictions can easily fall prey to sights and sounds of food advertising. Fr Paul notes that while all the senses can have this kind of impact on us, their relative strengths depends on our individual personalities. However in all of us, an experience in one sense can bring up another: a smell may trigger a sound or an image. He points out that there is a patristic tradition of confessing sins of sight, taste, smell and so on.

The false image – image without communion

Anne sees that in the image we present to the world, we all wear masks, and that part of what sanctification is about is gradually melting away our masks so that each of us can become the person God created us to be. She points out that icons are never painted in profile, avoiding eye-contact with the viewer, but always face to face with us. Anne wondered whether there is something in the nature of erotic imagery that invites “sideways glances, clandestine looks and meetings”, that perhaps the idolatry involved in pornography addiction darkens our souls, causing us to lower our gaze, turning away from the light of Christ. She quoted her Father Confessor speaking about Confession as turning the light on our sins: “It’s like flipping on a light in a dark room and watching the roaches run for cover.” She says, “We are just like roaches, when we allow ourselves to love darkness rather than light.”

Fr Peter saw a deep opposition between the common modern use of the word image to denote superficial presentation, with its associations with consumerism and materialism especially in the world of advertising, suggesting the surface and the reality can be very different. This is in sharp contrast to iconography, where a “presentation of the very depths of reality becomes accessible to us”. Pornography is likewise about manipulation, he says, where what is presented is for the immediate gratification of the person watching. Where there can be no depth of communion, it is a denial of true iconography.

Perhaps the heart of the opposition between pornography and iconography lies here, in the matter of communion. Fr John Breck say that pornography is a ‘demonic iconography’, and it perhaps is not going too far to describe pornographic images as icons of hell. The icon is there to draw us into deeper communion; the image is there as a window that we can pass through to a deeper reality. Pornography is there as a substitute for communion, as an ‘easy way out’ to gain the pleasure without the struggle of relating to another human being.

In pornography there is nothing to pass through and no deeper reality to find, quite the opposite; in pornography a human person, an icon of Christ, is stripped of that iconographic nature as the spirit is separated from the flesh, and the flesh presented as a commodity, an end in itself. In fact, while the icon brings us to a person, pornography begins to damage our very ability to relate on a personal level: there is an “absence of individuality in the figures of pornographic literature and imagery. In pornography, one human being is interchangeable with any other of the same general type… the medium which seems to represent ‘individuals’ – the photography of fashion and pornography – in fact imposes stereotypes for replication in social reality. Yet the icon, which makes no pretence at physical literalism, allows the viewer the freedom to find the individual beauty of particular human beings.”

So while iconography leads us into the communion of heaven, pornography destroys the communion designed by God for the human person as an icon of Christ, separates the image from the full personal reality of the person portrayed therein, and separates the sexual impulse from the essential aspect of communion for which it was created. Unsurprisingly, the end result of this is to damage the pornography user’s ability to experience any level of communion. As one of the women interviewed by Pamela Paul (for her book Pornified) put it, “I don’t know any man who is into porn who has been able to be truly intimate.”

Beauty will save the world?

One of Dostoevsky’s characters famously declared that beauty would save the world. Eugene Trubetskoi enlarged upon this idea: “Our icon painters had seen the beauty that would save the world and had immortalized it in colors. The thought of the healing power of beauty has been alive for a long time in the idea of the miraculously revealed and miracle-working icon! Amid our present manifold struggle and boundless sorrow, let that power console us and give us courage.” Anne says that icons are born in “the convergence of the beauty of the spiritual realm… with the beauty of the physical world.”

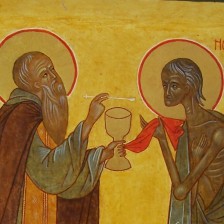

Anne recounted that back in the 1980s she heard a priest recommend to students the need to have an icon of the Mother of God on the wall in their dorm room particularly to aid with the struggle with lust. She also recommended that an icon of St Mary of Egypt could also be a good reminder of the importance of the struggle. Both Fr Peter and Fr Paul had suggested to people involved in a struggle with pornography that they keep an icon attached to the computer monitor. Though as Fr Peter points out, this is more a reminder than anything, and it is of course something people will be free to ignore or remove if they give into the temptation to do so. Fr Peter also now always makes sure to explicitly include televisions and computers when he is blessing a house. He can remind a penitent of this during confession, that the computer and television are not somehow outside real life, but should be swept up into one’s whole life in Christ and the Church.

When Fr Peter spent a few days on Athos, he says that even in just a few days, when what was before his eyes was limited to the iconography in the many hours spent in church, the beauty of the landscape when outside, and other real human faces, most of them committed to a lifelong struggle towards Christ, he felt the beginnings of a kind of retraining of where his thoughts and imagination would begin to go, teaching him to see reality on a deeper level, sanctifying his sight.

St John of Kronstadt highlighted our tendency to “… see flesh and matter in everything, and nowhere, nor at any time, is God before our eyes.” Granting that icons have the power to sanctify our sight, how far can this power be exercised if we are focusing our eyes on icons for only a little time each day, and letting our eyes rest on ‘flesh and matter’, as St John puts it, the rest of the day. The Definition of the Seventh Ecumenical Council said, “For the more these [Christ, the Theotokos, angels, saints and holy men] are kept in view through their iconographic representation, the more those who look at them are lifted up to remember and have an earnest desire for the prototypes.”

Pornography is a particular focus on flesh and matter, and a certain failure to keep ‘God before our eyes’. Pornography, says one former user, makes an object out of everybody. “It takes a three-dimensional human being with feelings – someone who could be your daughter, sister, or mother – and basically says, this is a creature that is only intended to satisfy your sexual desires. It becomes your natural way of thinking… You’re no longer conscious you’re even doing it. It just happens.”

Contrast this with what Metropolitan Kallistos says about the use of icons:

“As we gaze in our worship upon the transfigured cosmos of the icon, we actually enter within that new world, becoming one with that which we behold, filled with its grace and changed by its power. The purpose of the icon is thus not only contemplation but transforming union.”

If we immerse ourselves in the life of the Church, if our vision is sanctified by the constancy of our being surrounded by the iconography of the Church, if through this we can learn to look upon every human being as an icon of Christ, including those in pornographic images, then pornography must lose its power over us.

“From your icon, O Lord, we receive the grace of healing… the eyes of the beholders are sanctified by the holy icons.” (Triodion)

You must be logged in to post a comment.